1. Origins

The Santa Fe Trail was not a road; it was a collection of overland trade routes. It didn't go to northern New Mexico because New Mexico was not part of the United States at that time; it went to Old Spanish Nuevo México. It wound up in Santa Fe certainly, but it didn't start from a particular place; it started from various settlements along the Missouri River west of Saint Louis, centered on a five-county area of central Missouri known as Boonslick (Wikipedia, Boonslick) (Map).

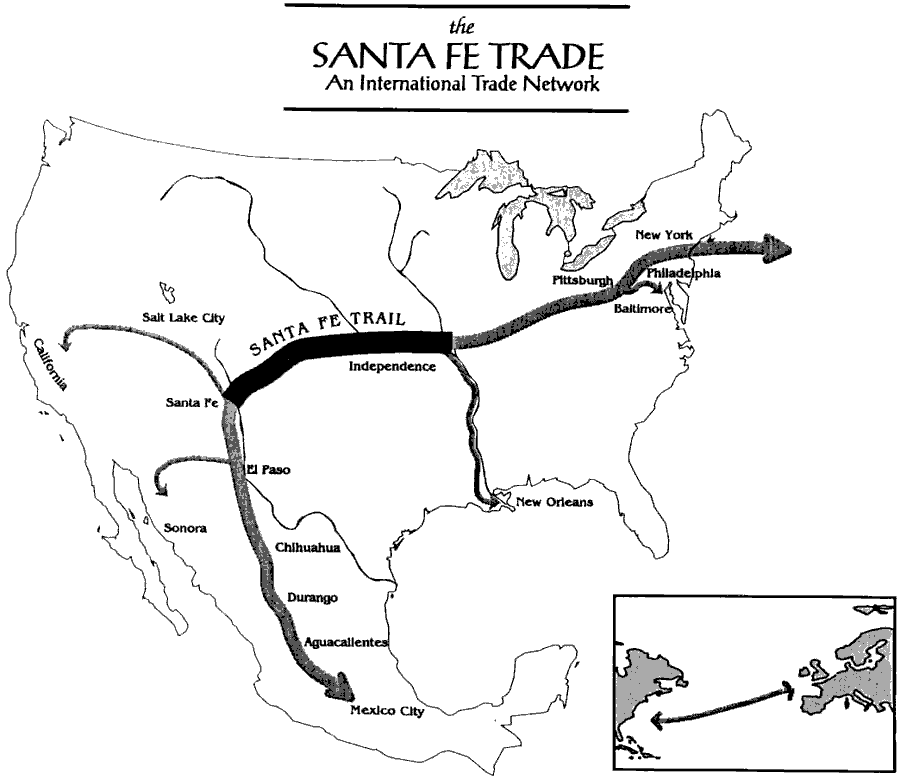

North American Trade Routes (Boyle). |

El camino real de tierra adentro (The Royal Road from the Interior Land) (Wikipedia, El camino real) (Map), on the other hand, was an improved road between Ohkay Owingeh (San Juan Pueblo), Nuevo México, and Mexico City. The capital of Nuevo México, Santa Fe, was on that road as were Durango and Zacatecas in Mexico. Although merchants from Nuevo México had been trading to the south for decades, the Santa Fe Trail allowed these places to become destinations of traders from the United States, too (Wikipedia, Chihuahua Trail). The stunt that made the Santa Fe Trail an economic phenomenon was linking El camino real with the Missouri River.

1.1. Hard Times

Times were hard in Santa Fe in 1821. Mexico had achieved final independence from Spain in September, but Spain continued to blockade port cities, causing a shortage of manufactured goods from Europe (Wheeler, Life of William Becknell).

Looking north from the heights above Boonville, MO. The Missouri River is in the foreground, the Boonville Municipal Airport is beyond, and somewhere on the higher ground north of the flood plain is the site of Franklin, MO, the erstwhile jumping-off point of the Santa Fe Trail. Wed 09 Sep 2015 01:06PM, Fullsize 288KB, Map. |

Times were hard in Missouri, too. The inept response of the Second Bank of the United States to the Panic of 1819 had destroyed public confidence in federal monetary policy and caused a persistent liquidity crisis (Wikipedia, Panic of 1819). In August of 1821 Missouri had been admitted to the Union as a slave state as part of the Missouri Compromise.

William Becknell was on probation for owing money. He was in the same situation with a lot of people around Franklin, MO, who controlled plenty of property (including slaves) and who had no cash at all, but he was one who decided to do something. Europe was dumping manufactured goods in the New World such as printed cloth. He scraped together $300 worth of trade goods and headed west with a pack train in September. He stayed a couple of weeks, selling his merchandise in Santa Fe, and was back in Franklin by late January. On the day that he returned, he took a seat on the boardwalk and, slitting open a rawhide bag full of Spanish silver coins, settled with all his creditors on the spot. He brought back about six thousand dollars (Wheeler, Life of William Becknell).

Silver peso of Carlos IV (Coinman62). |

Here are the coins that Becknell bartered for in Santa Fe, the Spanish pesos de ocho (one ounce, eight-real weight coins) or pieces of eight, which you've heard of, no doubt. (Cap'n Flint, Long John Silver's parrot, was always squawking about them in the British book about pirates, Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson, which was published in 1881 but set in the 1750s.) The Spanish peso was an international currency, and, because the United States minted so little of its own coinage, American creditors accepted silver bullion coins like Spanish pesos, which circulated on par with one-ounce U.S. silver dollars (Wikipedia, Spanish Dollar).

1.2. Big Success

Becknell and others ran considerable risk, traveling overland to Santa Fe. Personnel, draft animals, and cargo were exposed to the elements, and too much water and too little were abiding concerns as were too much heat and too much cold. There were uncertain domestic politics and foreign exchange rates. There was the ever-present threat of robbery from gangs of hoodlums and freedom fighters along the trail. There was the chance of getting lost. And, no matter which end of the trail you started from, there was a language barrier at the other end. Becknell himself spoke no Spanish.

Nevertheless, bringing circulating specie back to the communities of Boonslick boosted the local economy immediately. As soon as he could plan the next trip, Becknell was back on the trail to Santa Fe -- this time with wagons. He issued shares to help pay for ten times as much merchandise. He left at the end of May in 1822 and returned in mid October. The profit from his second trip was about $91 thousand! A school teacher who had subscribed $50 received $912 for her share (Wheeler, Life of William Becknell).

1.3. Big Business

After that, profits returned to earth as the market for manufactured goods in Santa Fe was saturated and all the loose cash in that town was soaked up. Becknell had his imitators, some of whom had left within days either side of his departure.

There were traders from Nuevo México and Chihuahua, too, who were financed not by corporations but by wealthy families (Wikipedia, Santa Fe Trail). Bent, St. Vrain & Company headquartered in Taos, Nuevo México, fit this pattern (Wikipedia, Ceran St. Vrain).

Surviving documents, such as manifests and guías, do not allow an accurate and systematic comparison between American and New Mexican shipments. It is also impossible to establish the size and value of the merchandise that remained in the territory. Guías often do not provide information on the value of the goods. Customs officials seldom prepared complete manifests for an entire year and, as Moorhead noted, these documents bore little relation either to the amount or the assessment of the imports. Although it is not possible to assert that New Mexicans controlled the trade on the eve of the Mexican War, it is accurate to maintain that during this period New Mexicans were the majority of the traders traveling down the Royal Road to the interior of Mexico (Boyle).

Like Becknell, they followed Indian trade routes between the Great Plains and the Rio Grande Valley, which had persisted through the Spanish conquest from prehistory (U.S. National Park Service, People of Pecos); nevertheless, sending heavy wagons along overland routes back and forth between Missouri and Nuevo México was a new thing. It coincided with the beginning of the Rocky Mountain fur trade on the Missouri River, which eventually opened the emigrant trails to Utah, California, and Oregon from jumping-off points between St. Joseph, Missouri, and Kanesville, Iowa (now Council Bluffs). But there was enough opportunity for trade over the Santa Fe Trail to hold the interest of merchants from Missouri and from Nuevo México for decades.

As steamboats became more prevalent and affordable on the Missouri River and as the need for larger warehouses evolved, the head of the Santa Fe Trail kept shifting evermore westward from the Boonslick area to Lexington, Independence, and Kansas City in Missouri and eventually to Fort Leavenworth in Kansas.

Economies of scale drove out individuals in favor of better financed organizations that could invest in more and bigger wagons, insure against loss, and hire security personnel.

Then came the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway, and the head of the Santa Fe Trail began following the end of track westward through Kansas. The railroad arrived in Dodge City in 1872, a place that would become famous a few years later as a destination for cattle drives from Texas.

Santa Fe Trail business grew very big very early and continued its trajectory until it was superseded entirely by the railroad in 1880. In 58 years at least $100 million of business must have been transacted over the trail (Wheeler, History).

1.4. Trade Goods

Manufactured goods went west and hard currency and raw materials came east. Manufactured goods included cloth produced in the mechanized factories of New England and Europe. Probably it was cotton stuff -- more or less colorfast -- that my folks would have called gingham, which was made of colored thread, and calico, which was woven of plain thread and printed with colored patterns afterward. Neither of these seem especially expensive or desirable today, but in the late 18th and early 19th centuries they were technological marvels.

In addition to bolts of fabric, other manufactured goods consisted of finished clothing, housewares, tools, prepared food and coffee, medicine, liquor, books, matches, and firearms.

Raw materials produced in Old Spanish Nuevo México included gold and silver, fur, and buffalo hides.

As the U.S. Army's presence along the trail grew between the Mexican-American War and the Civil War and even afterward, more and more of the traffic along the Santa Fe Trail was composed of federal military supplies (Wheeler, History).

1.5. Missouri Mules

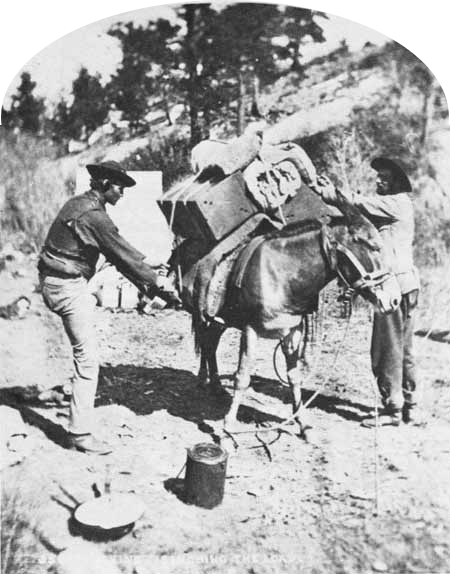

"Sinching" the Load (by William H. Jackson, 1875) (Boyle). |

Spanish-bred mules and donkeys were part of the influx of trade from Santa Fe to Missouri, too. The mules were both a commodity and source of motive power for traders in those days, and the demand for more mules grew with the need for hauling more goods. Missouri farmers began breeding their own out of the donkeys obtained from Santa Fe (Wheeler, History), and the term "Missouri Mule" entered the American lexicon. By the time the railroad had taken the place of the Santa Fe Trail, the phrase had come to mean "stubbornly independent" as applied to anyone or anything. This was ironic. Not only was the market in domestic mules an outgrowth of international trade relations, but also it demonstrated an economically adaptive interdependence -- and ultimately a hybridization -- between the English-speaking culture of the American Midwest and the Spanish-speaking culture of the American Southwest.